When Brian Eno released his Generative Music 1 album — music that is created ‘on the fly’ by a computer following a set of rules that Eno programmed, released on floppy disk, and now virtually unplayable on any current hardware — he wrote “I really think it is possible that our grandchildren will look at us in wonder and say: ‘you mean you used to listen to exactly the same thing over and over again?'”.

When Brian Eno released his Generative Music 1 album — music that is created ‘on the fly’ by a computer following a set of rules that Eno programmed, released on floppy disk, and now virtually unplayable on any current hardware — he wrote “I really think it is possible that our grandchildren will look at us in wonder and say: ‘you mean you used to listen to exactly the same thing over and over again?'”.

If you were feeling mean, you might classify a strand of Bill Drummond’s musical output as an agitprop popularisation of some of Eno’s ideas. 17 fits that profile, as Drummond wants to play his part in getting rid of recorded music and perhaps not just recorded music. “Imagine waking up tomorrow, all music has disappeared,” begins one of his many manifestos. He declares Year Zero in the history of music, razing what has gone before and starting again — and all of this single-handedly, or with a bit of help from some travelling companions and some yet-to-be-convinced schoolchildren.

What’s interesting about the campaign Drummond conjures in 17 is that it re-interprets the current state of the recording industry not as a commercial crisis, but as a cultural one.

recorded music has run its course, it has been mined out. It is so 20th century, like paper money and fossil fuels… all (or should that be 99.99 percent?) of music being written, composed, created [is] done to be recorded, and once recorded, to be experienced in a very limited way.

The first hundred or so pages are carried by Drummond’s commitment to asking the basic-but-necessary questions and articulating his discontent:

What is music for? And why do we listen to it in the way that we do? And what would it be like if…? But the big questions seemed to be ‘Why am I so frustrated with it?’ and ‘Why do I want it to be something other than it is?’ and ‘Why do I want it to exist in some other sort of way than it already does?’

One of the causes of the frustration is the simple ubiquity, the super-abundance of recorded music in the 21st century. This is something I’ve touched on intermittently on this blog over the last four years: the diseases of affluence that mean that we throw away more recorded music than we used to own a generation ago; the other critics who have reported feelings close to nausea from over-listening, and the research indicating that “accessibility and choice has arguably led to a rather passive attitude towards music heard in everyday life”; and one of Drummond’s own antidotes in the form of No Music Day (which is coming around for the fourth time next week).

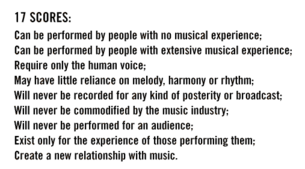

17 goes into more detail about No Music Day, but the main strategy he explores and documents in the book is the one that provides its title. Drummond writes a number of poster scores to be performed by ensembles of 17 people, who mostly have not met before, in different configurations, using only their voices. These performances are recorded and played just once, and then the recording is destroyed.

17 goes into more detail about No Music Day, but the main strategy he explores and documents in the book is the one that provides its title. Drummond writes a number of poster scores to be performed by ensembles of 17 people, who mostly have not met before, in different configurations, using only their voices. These performances are recorded and played just once, and then the recording is destroyed.

The first third of the book also explains what’s behind these scores, for example in terms of Drummond’s love of choral music (like Arvo Pärt’s), and clarifies that, no, really, he’d never heard of Cornelius Cardew, Fluxus or Stockhausen before other people pointed out the similarities between his work and theirs — but since this has now been drawn to his attention, he’s looked into their work, and it is indeed good stuff.

Drummond loves to tease with this kind of self-mythologising, slyly putting his work in the context of avant-garde pioneers while claiming to arrived at the same place independently, and daring us to accuse him of stretching the truth (I know art colleges did little traditional teaching of art history in the ’70s, but don’t you pick this stuff up through osmosis and natural curiosity? As a science student, I’m sure I knew about all those people by the age of 22).

This is quite fun (if not quite in the same class as the personal stories in Drummond’s wonderful 45) but the mythologising is really all that carries the last 250 or so pages of the book. It adds spice to the musical autobiography and the diary of different performances of the 17 scores — which is just as well, because the number of new ideas about music tails off dramatically, and these stories would be pretty dry without Drummond’s nagging chutzpah (or as the director of a gallery and music festival calls it, “high jinx”). He loves to make a grand claim and then expose his insecurities about it. At times, he can’t seem to help himself: expressing a compulsion to graffiti, literally, his ‘notices’ at the side of major roads; being convicted for driving while banned — and then displaying the brilliant resilience to enjoy his sentence of 60 hours community service digging ditches, described as “good honest hard work… just what you need to get fit and get your head clear for serious thinking.”

Drummond also takes evident pleasure in quoting, approvingly, an email that concludes by summing up all his work as “raving narcissism”. “Well, I suppose it is all about me,” is his rejoinder. Elsewhere, the device of having multiple voices commenting, challenging and contradicting the author seems a bit tired and conventional these days, but at the end I found myself nodding in relieved agreement with the critique of the 17 project that is attributed to Drummond’s long-time cohort, Dave Balfe; in particular, “if you had been using a modicum of self-discipline you could have got it all down to a 2,000 word essay”. Balfe goes on to argue that Drummond’s professed desire to “accept the contradictions” in his work is not a sign of great art so much as lack of discipline and rigour.

I say “attributed to” Balfe because, in common with one of the other paratextual commentators in the book, I suspect these criticisms are largely Drummond’s own, a reflexive doubling of his acceptance of contradictions.

If so, I’m tempted to reply that you and I have been through that, and this is not our fate, so let us not talk falsely now.

The truth is it’s not just music that is suffering the problems of cultural surplus. The palate gets jaded when the stomach is already sated. How much is the world crying out for another blog post about another book about another possible future for music?

At the heart of 17, what binds the ideas to the autobiography is a struggle to break the cycle of just producing more of everything; to make culture new, fresh and strange again. The book seems to concede failure in that grand ambition, but in so doing it reinforces the value of that ambition. No wonder Brian Eno has a copy on his shelf.